Why would anyone measure spine posture at work? Ergonomics consultants do not really measure the position of your spine at work, so why start now? Laboratory and clinical research precisely measure spine posture with very sophisticated and fully calibrated equipment. Clinically trained people who treat the spine know where the spine works best. Rarely do we have that kind of equipment or talent to find the best posture where we need it—where people do the work—at the office, in the car, on the job.

We mostly presume the problem of sitting will be solved if only we get a well-designed chair, and then get it adjusted exactly right. Modern chairs are designed for good comfort and support—why do people still get neck and back pain from sitting? What is it about sitting that also increases the health risks for diabetes, obesity and heart disease?

The research is clear that it is not sitting that is the problem, but it is the way we sit that causes trouble1, 2. When we look closely, there is a very small observable difference between the very best spine posture and the very worst spine posture, even using the same “ergonomically adjusted” chair3. The full range of motion from best to worst posture is only about 20-30 degrees of movement. When the “worst posture” is sustained for very long, we get stiffness and pain in the spine4, and we increase the risk of diabetes, obesity and heart disease5.

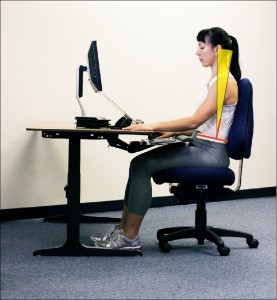

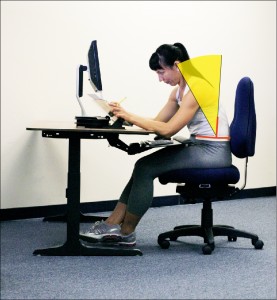

Photographs 1 and 2. The top image shows the ‘recommended’ reclined sitting posture with good spine posture and low disc pressure compared to standing. The bottom image shows the same chair adjustment, but the very worst posture, doubling lumbar disc pressures6, and increasing risk of long-term spinal problems.

A simple movement to teach good spine position has been used in the clinic for decades, usually as a way to start exercise, but it is also a painless way to show when we have good posture. It can be done without technical training or equipment, and does not need detailed measurements. Rather than finding a particular angle, it is movement that shows when the spine is in the best position.

If you are sitting now, just try to sit up taller—gently pull the shoulders backward while lifting the center of your chest. When the body can move freely, the taller sitting movement will cause a gentle forward rotation of the pelvis and slightly increase the arch in the low back 7. We could call this movement an exercise, or a postural cue, or maybe a “reset” position for the spine. It is this gentle movement at the waist that indicates the base of the spine is in the mid-position, or “neutral” posture8. When forward-backward bending movement available in the spine, the postural muscles can work and the spine can stay healthy9. The goal for seated ergonomics is to make it easier for the spine to work in the best position, and avoid the worst postures. Good chair position will easily allow this movement during the work routine.

If the chair is reclined, and the work draws the upper body forward, the low back is usually stuck in the worst position of forward bending, as though the body is bent over to touch the toes. When this slumped posture is held for more than five seconds, the deep postural muscles completely relax, and the ligaments begin to stretch10. Sustained slumped posture causes the musculoskeletal problems of stiffness and pain. It is the sustained lack of the postural muscle activity that increases long-term health risk.

Chair adjustment is very important to do work that draws the upper body forward, and a short video will show how chair adjustments can support better postures. An appropriate chair can make good spine posture easy for both forward and reclined tasks, but we must make a conscious choice to change the adjustment. A properly adjusted chair and work surface can allow active movement through the legs and torso to make movement easier, make back pain less likely, and the best postures will be easier to sustain. When we measure spine posture we can change it.

Compared to the pain of slumped sitting, standing improves the spine posture, there may be some perceived improvement in comfort11 and the postural muscles are more fully engaged. Unfortunately, increasing the body’s effort to stand increases other health risks(12-14), and there may be a much greater cost to change the workplace.

Somebody’s mother was exactly right—it is a good idea to “Sit up straight!” We can easily measure spine posture where we work with a very small movement. That spine posture measure will show why some chairs may not work very well, and give us more evidence to make better choices for the chair and the chair adjustments.

Next, look for: “Why measure postural muscle strength?” Our post will show how to find the strongest position for the postural muscles to make the best postures easier to sustain, and lower the long-term health risks associated with sitting.

John Fitzsimmons is a Certified Industrial Ergonomist and a Physical Therapist skilled with treating musculoskeletal injuries. He is the principal consultant for Ergonomics First, Inc.

References:

- Hamilton M, Hamilton D, Zderic T, 2004. Exercise physiology versus inactivity physiology: an essential concept for understanding lipoprotein lipase regulation. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 32: 161-166

- van Uffelen J, et.al., 2010. Occupational Sitting and Health Risks, A systematic review. Am J Prev Med (39) 379-388

- Fitzsimmons J. 2014. Improving field observations of spinal posture in sitting. Ergonomics in Design (22) 23-26

- Mork P, Westgaard R. 2009. Back posture and low back muscle activity in female computer workers: A field study. Clinical Biomechanics (24) 169–175

- Owen N, Healy G, Matthews C, Dunstan D, 2010. Too much sitting: the population-health science of sedentary behavior. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. (38) 105-113

- Wilke HJ, et al., 1999. New in vivo measurements of pressures in the intervertebral disc in daily life. Spine 24: 755-762

- Dunk N, Kedgley A, Jenkyn T, Callagahan J. 2009. Evidence of a pelvis-driven flexion pattern: are the joints of the lower spine fully flexed in seated postures? Clinical Biomechanics (24) 164-168

- Panjabi M, 1992. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypotheses. J Spinal Disord (5) 390-397.

- Freeman M, Woodham M, Woodham A, 2010. The Role of the Lumbar Multifidus in Chronic Low Back Pain: A Review. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2: 142-146

- O’Sullivan P, et al., 2006. Evaluation of the flexion-relaxation phenomenon of the trunk muscles in sitting. Spine 17:2009-2016

- Karakolis T, Callaghan J. 2014. The impact of sit-stand office workstations on worker discomfort and productivity: A review. Applied Ergonomics (45) 799-806.

- Krause, N, et al, (2007). Occupational activity, energy expenditure and 11-year progression of carotid atherosclerosis. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Environmental Health 33, 405-424

- Wilks, S, Mortimer, M, Nylen, P (2006). The introduction of sit-stand tables: aspects of attitudes, compliance and satisfaction. Applied Ergonomics 37, 359-365.

- Tüchsen, F, Hannerz, H, Burr, H and Krause, N (2005). Prolonged standing at work and hospitalization due to varicose veins: a 12-year prospective study of the Danish population. Occupational Environmental Medicine 62; 847-850.